METU FLE ELT Talks - Session 20 (Prof. Michael McCarthy)

Session notes:

"In teaching English, we often make a distinction between what we call the productive skills and receptive skills. Productive skills are considered to be speaking and writing, while receptive skills are listening and reading. I want to question that division that divides things into receptive and productive. I think listening is, in fact, a productive skill. It's a very active skill, not just a question of reception. That is why I call speaking and listening to the two sides of the same coin; all the evidence suggests that you cannot really separate them."

The quote above belongs to Professor Michael McCarthy, our lovely guest for the 20th session of METU FLE ELT Talks. McCarthy shared his findings and insights regarding how we can use the corpus to understand the relationship between speaking and listening, especially in everyday language use. When communicating with others, we all have specific roles, such as the listener or the speaker. However, McCarthy emphasized that when examining the corpus, it becomes visible that the performance of such roles is actually quite complicated.

"One of the problems is that listening in the language classroom is different from listening in conversation. In a language class, the emphasis is typically on the content. What you can hear and understand, and you will be tested on your understanding. You listen to something, you answer a question about it, and you can be right or wrong."

While nothing is wrong with that notion, McCarthy added that listening in conversation does not solely have the goal of comprehension; it focuses on interaction. "We listen in order to be able to interact. We do not worry about examination while we talk to our friends since they are not going to give us a multiple-choice test about the last holiday they were mentioning to us."

In our conversations, we show that we understand by the way in which we respond. In other words, understanding is not the only thing we do; we also show it. So, the listener is also the speaker. Apart from the very beginning of it, everything in a conversation is just a response to what you just heard." Although it is a simple statement, it has significant implications.

The structure of a conversation is simple: there are at least two parties involved, it is usually face-to-face, while it could also be digital, and crucially, it is in real-time. "Someone says something, and it is gone. You can ask them to repeat it, but usually conversation flows." Also, the roles of speakers and listeners constantly change while the listeners show that they are listening. But how exactly do listeners do this? There are multiple ways, such as using body language, acknowledging the contributions of the speaker, and, most crucially, connecting what the speaker has said to what they will say.

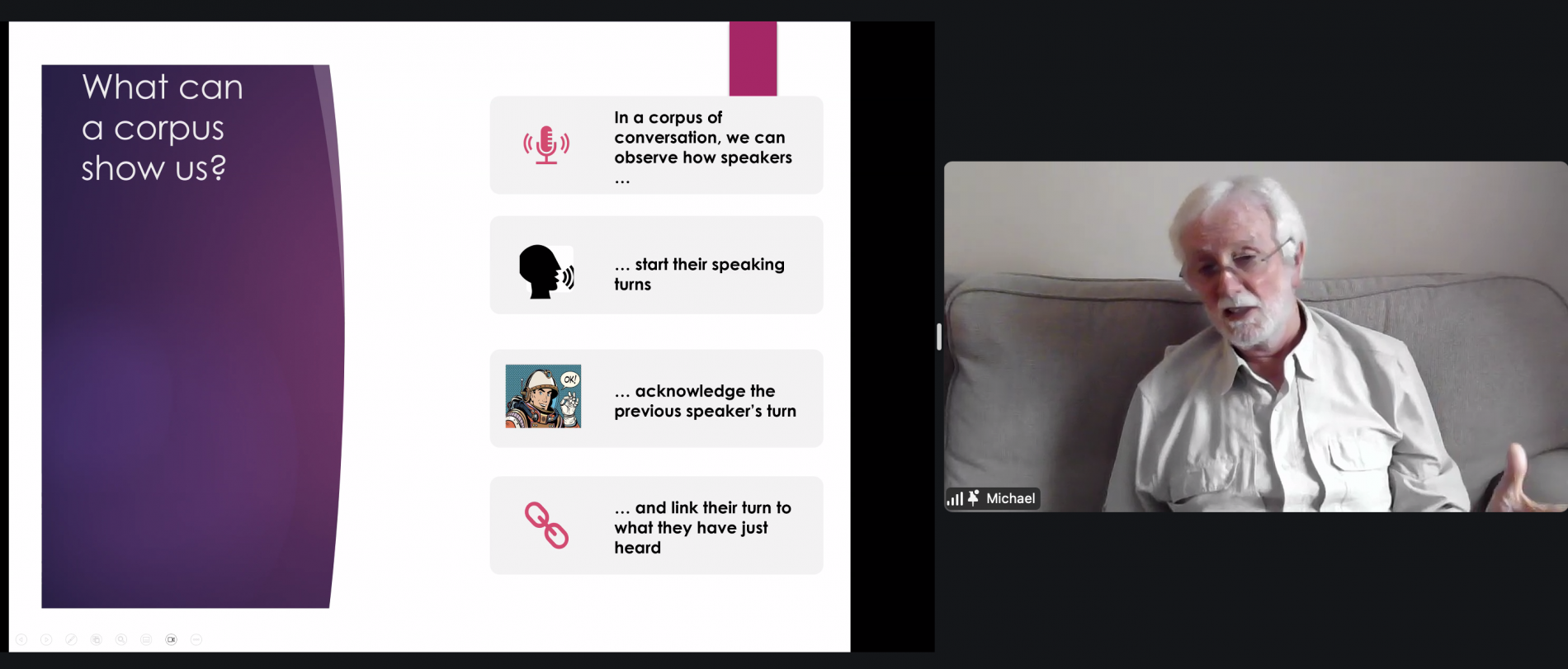

Then, how is the corpus useful or related to this? McCarthy explained that the corpus of a conversation can allow us to observe how speakers do various things, such as how they start their speaking turns, acknowledge the previous turn, and link theirs to what they have just heard. Therefore, corpus creates a guideline for us to see patterns, often used words, and the order in which we say and respond.

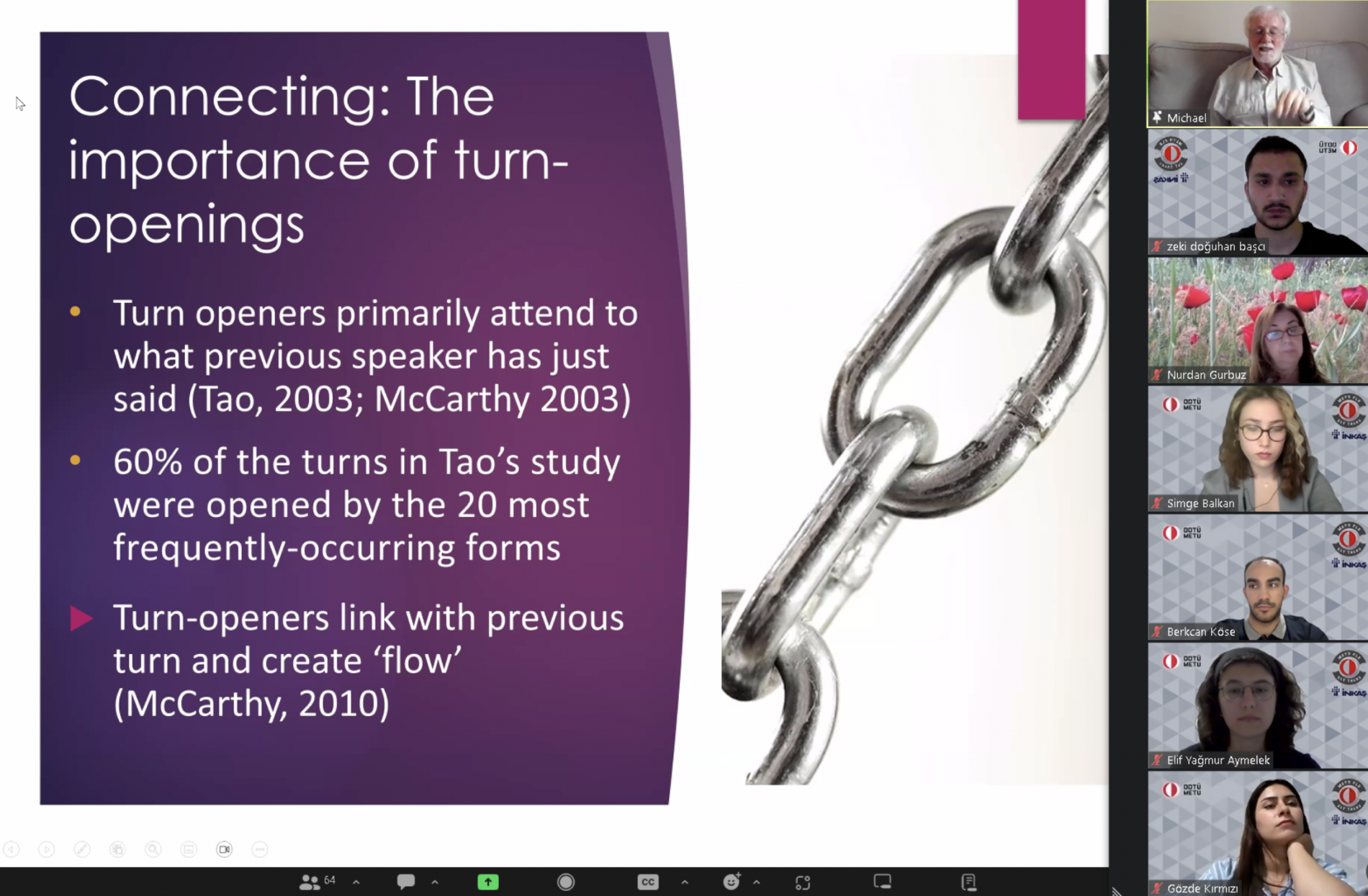

According to the research McCarthy conducted with Tao, turn-openers primarily attend to what the previous speaker has just said. Also, 60% of the turns in the study were opened by the 20 most frequently occurring forms. Some examples are yeah, well, and right. "When you think about all of the possible words you could use to start your turn, there are millions of them. Yet, there are only about 20 of them that people use all the time. Regardless of what you are talking about."

We can even use short sounds such as "uh-huh" or "hmm" to show that we are not just listening to the other party but are engaged and involved with the conversation. "Certainly," "Wow," "Oh no," "Right," "Really," "No way..." As McCarthy mentioned, many more can be given as examples to them, and they are called non-minimal tokens. These response tokens show not only comprehension but also acknowledgment and engagement, and they do more than just a simple yes or no. Overall, when the corpus is analyzed, there is a preferred sequence as certain words do not occur randomly; as McCarthy puts it, "there is a pecking order."

Then, how do we apply this notion to our classrooms? "It seems to me that what we need is more materials that will encourage response," McCarthy said and provided multiple solutions and implications: giving our students opportunities (such as pair and group work) to react appropriately, not just having listening comprehension exercises, teaching the lexical/grammatical repertoire of responding and mainly introducing learners to the notion of listenership and grammar of turn-taking.

To conclude, here's a final quote from McCarthy that he would say endlessly, as it encapsulates everything: "Listening is all about connecting with what you just heard and connecting it with what you are going to say. And when you speak, your first duty is to show that you listen. That is why they are the two sides of the same coin."