METU FLE ELT Talks - 26. Oturum (Dr. İlknur Civan Biçer)

Oturum notları:

"As language teaching professionals, we wear various hats: educators, mentors, advisors, collaborators and sometimes even mediators. Among these, mentoring stands out as a cornerstone for professional development and mutual growth."

The quote above belongs to Dr. İlknur Civan Biçer from Anadolu University, whom we had as our wonderful guest, perfectly fitting for the 26th session of METU FLE ELT Talks. Biçer invited us to the wide world of mentoring and the position (im)politeness with a reflective lens. She started the session by providing a quick insight regarding the word choice "Grace" in her title, explaining that "I think the word 'Grace' is very important for me because mentoring requires not just knowledge or expertise but also empathy, support, and the ability to navigate the delicate balance between providing guidance, and empowering mentee student teachers."

Our deep dive consisted of two theoretical frameworks: Mentoring in ELT contexts and the concept of politeness/impoliteness. Biçer mentioned that although these frameworks are rooted in linguistics, their relevance goes beyond the theory and can directly relate to our mentoring conversations, especially during feedback. Therefore, mentoring in ELT is not solely about sharing teaching techniques and pedagogical strategies since it aims to shape reflective practitioners who think critically and grow professionally. Connectively, as mentors, we should also be aware of our communication style: our choice of words, our tone, and our approach since all of them affect the confidence, motivation and growth of those we mentor.

"One of the most significant challenges I have experienced so far is maintaining effective communication with mentees, especially when giving feedback and guidance. Because this process carries the risk of being perceived as overly critical, dismissive and even impolite." Biçer shared that this observation was one of the main reasons she got into the world of mentoring in ELT and started investigating the relationship between language use and mentoring.

A definition regarding who exactly is a mentor is also needed. When we have a deep dive into the world of mentoring in ELT, the first aspect that happens to be clear is its multifaceted nature. A mentor is not just an advisor but also a dynamic guide who fulfils multiple responsibilities. Mentorship is also connected to the concept of scaffolding, facilitating a bridge between theory and practice for novice teachers. Mentors gradually remove their structured support as the mentee grows in competence, confidence and teaching abilities. As Biçer highlighted, mentors are seen as fundamental figures in the development of mentees as they play a central role in shaping professional identities and fostering confidence.

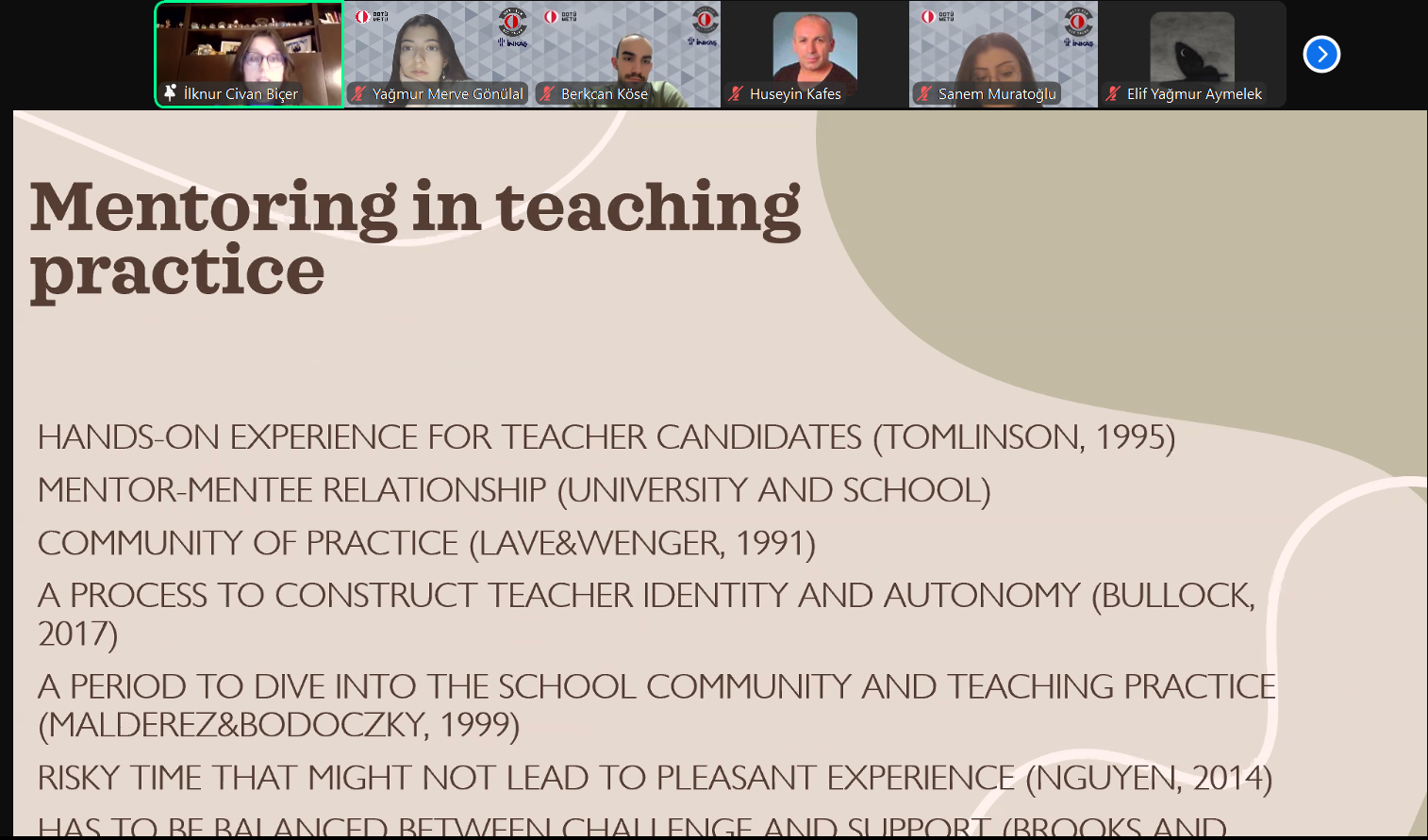

Teaching practice is a cornerstone for the teacher education process, offering invaluable opportunities for teacher candidates to develop their skills and styles in real-life contexts. As the teacher candidates slowly build their teaching philosophy, mentoring plays a pivotal role as a collaborator, sponsor and guide for students. Teaching practice is also a significant chance for teacher candidates as it provides hands-on practice and the room to transform theoretical knowledge gained so far while actively engaging the practicalities with classroom management and student interaction. Therefore, it can be said that providing support as they build the connection between the theory and their classroom can be effectively done through mentoring, further showing its significance. In addition, mentoring during teaching practice is crucial for teacher identity and autonomy. Biçer mentioned that this is perceived as a process where teacher candidates begin to envision themselves as professionals and develop their unique decision-making styles, shaping their future educator roles. They also dive into the school community and its culture, interacting with the school administration and other teachers.

Yet, Biçer reminded, that teaching practice can also be an immensely stressful and challenging time for teaching candidates. It can be risky for some candidates primarily due to the pressures of performance adaptation, and feedback may not always lead to pleasant or constructive experiences. Mentoring, therefore, becomes even more critical to ensure that these challenges are framed as opportunities for growth rather than sources of discomfort and discouragement. Mentors encourage them to step out of their comfort zone and embrace the realities of teaching while providing a safety net to help them navigate. In a nutshell, as Biçer perfectly described, "It is more than supervision; it is an active, intentional, dynamic process."

Feedback and mentoring are highly closely related. Feedback is one of the most essential and powerful mentoring tools, especially within the context of teacher education. It offers vital insights for teacher candidates to reflect upon. As Biçer notably stated, "I consider it very important despite the general focus of post-observation feedback sessions in the literature. I also want to share that pre-observation feedback sessions are also very important in encouraging teacher candidates in their practice since they enable them to feel more motivated, more confident, and safer." Mentors play an essential role in the development of successful teachers. As a mentor, you offer targeted, constructive, actionable feedback. However, feedback is not just for identifying technical skills or classroom strategies. Additionally, it is important to have a sense of belonging and professionalism. The importance of being seen as a colleague is highlighted in the literature, and every year, many teacher candidates express that even being able to get in the teacher's room is highly valuable for them. This recognition is especially vital since it shows they are valued, respected and contributing.

Speech acts carry a huge role as mentors frequently engage in them while giving feedback. For instance, complementing can boost confidence, whereas criticising can lead to defensiveness and discouragement. They even tend not to accept what is said. As mentors, mitigation strategies, such as softening critiques with positive framing or using collaborative language, are crucial to maintaining trust and open dialogue. Biçer provided an excellent example, saying that "Instead of saying your lesson was poorly structured, you can say that I noticed some great ideas in your lesson; perhaps we can work on organising them for maximum impact. First, you softened your critique; you still criticised but in a much softer way. This approach not only preserves their dignity but also reinforces the idea that mentoring is a partnership rather than a hierarchy. I should add that based on my own experience, I agree with the notion that every mentor has a unique linguistic style that can significantly influence the mentoring experience. This style does not only affect how they perceive you as a mentor but also how they internalise the feedback they receive."

Generally, mentors navigate between two communicative strategies: self-enhancement and self-effacement. These strategies are key to building rapport and mutual respect. While self-enhancement might involve asserting expertise and authority, self-effacement emphasises humility and inclusivity. So, the balance is crucial. We should also be aware of the perlocutionary effect and emotional influence of our language on our mentees. This awareness reduces the risk of damaging the face of the teacher candidate.

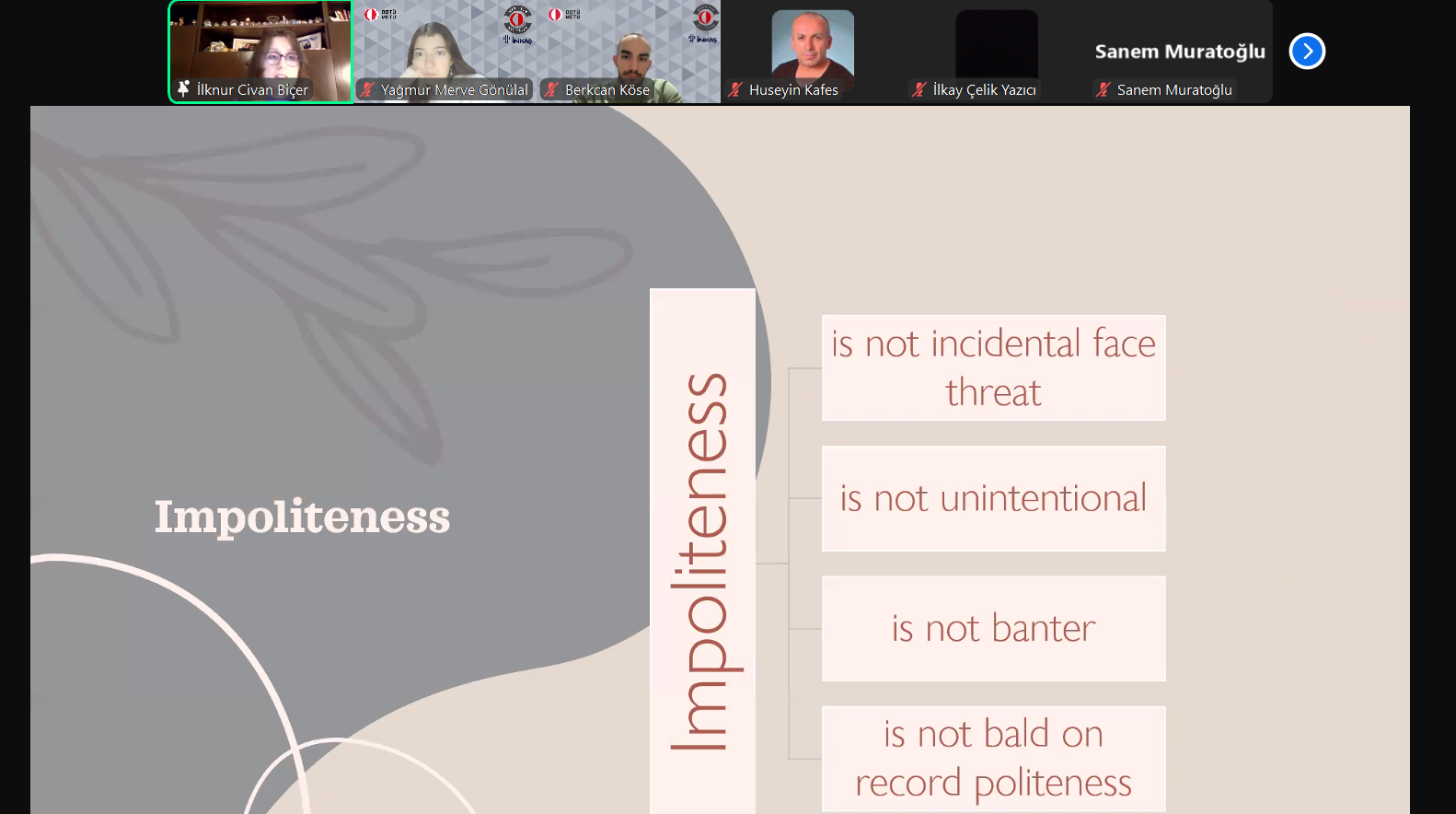

In the existing literature, we already see politeness strategies helping to gain a positive force in fostering trust, motivation and collaboration. On the other hand, even unintended impoliteness can create tension, misunderstandings, or communication breakdowns. Another key aspect to keep in mind, according to Biçer, is that politeness is highly culture and context-dependent. She also mentioned the face concept, a foundational theory regarding individual self-image. Through further elaboration by Brown and Levinson, two face types were introduced: negative face (about the personal desire for autonomy and desire and positive face (desire to be liked, approved or appreciated). Mentoring interactions involve a delicate balance between addressing these two faces. Providing constructive criticism may threaten a mentee's positive face while giving overly prescriptive advice could infringe on their negative face. Politeness, therefore, is not just about using certain words or phrases; it is about how the face is constructed, projected or attributed. In mentoring, face-threatening acts are inevitable. Such situations need careful mitigation. In the case of impoliteness, it might arise unintentionally, but its impact can be mitigated through careful, empathetic communication.

In essence, the mentoring process within the ELT world is a dynamic and multifaceted endeavour. It demands professional expertise and thoughtful awareness of how every word, gesture, joke, or even a moment of silence may influence teacher candidates' confidence and professional identities. While challenges will inevitably arise, especially around providing constructive criticism and managing cultural expectations of politeness, these obstacles make mentoring so meaningful. By striking a balance between expertise and empathy, mentors can create a supportive atmosphere where mentees feel encouraged, guided, and empowered to discover their potential. Ultimately, this positive engagement fosters a vibrant teaching community where mentors and mentees thrive through growth, reflection, and shared enthusiasm for lifelong learning.