Session notes:

For our 22nd session of METU FLE ELT Talks, we had the honor to have Dr. Yasemin Tezgiden-Cakcak with us as our dear guest. From the foundational introduction to inspiring implementation techniques, we have delved into the comprehensive world of critical pedagogy for this session's agenda. Let us start with a direct quote from Tezgiden-Cakcak regarding how her passion for critical pedagogy started:

"As someone who came from a small conservative town where I had the chance to meet with some critical teachers, this later encouraged me to have some critical perspectives. Inspired by them, I always wanted to pose questions in students' minds. I wanted them to think critically."

When it comes to critical pedagogy, we should begin by considering the educational issues we often face, maybe even daily! At the beginning of our session, Tezgiden-Cakcak created some room for a thought-provoking brainstorm regarding these issues to be shared. Some of the issues raised were inflexible curriculum, inaccessible resources, standardized assessment, discrimination, politically shaped education system, and so on.

Many issues such as these have been raised, can be raised, and will be continually raised within educational settings. But how about coming up with suitable and inclusive solutions? What might be the reason there is quite a difference between the number of problems we face and the number of solutions we can develop? Tezgiden-Cakcak highlighted this point by mentioning several options: Could it be a competency issue? Is it related to not having enough qualified people? Or might it be connected to creativity? She answers this question by referring to the critical pedagogy theory: "The problem is the capitalist, imperialist, patriarchal system. Education is organized according to this system, controlled by the %1 for the remaining %99. Why exactly is this the case? The answer is clear: When a severely exploited private school teacher goes against the system, they face several institutions trying to stop them. They might also face other institutions called ideological state apparatuses, such as media, culture, religion, or family."

Why are we mentioning these social aspects? Tezgiden-Cakcak answers this question by noting that, as educators, we consent to all of this since education is also a part of the ideological state apparatuses. As educators shaping our young minds, if we were to accept everything the way it is as of right now, and our education continues to serve this capitalist system, then what exactly is the purpose of education? While it aims to create a hard-working and competitive workforce that the system needs, it also highly desires them to be obedient.

The concerning part is that almost all of us are already familiar with different established forms of obedient behavior in our educational lives, such as being afraid to be put on the list of students who spoke while the class waited for the teacher. As Tezgiden-Cakcak further commented, "We learn to be obedient in school with these hidden curriculum elements."

There are also other problematic sides of the current educational system that critical pedagogy highlights, such as possible differences in the students' socioeconomic backgrounds. If you are born into a lucky family, you might climb up the ladders easily, but if you come from a more disadvantaged background, you may see the other people climbing the stairs and putting the blame on yourself. In addition to students, schools also hold great power as social and political sites to further influence the students based on the person's ideology, who has the most significant power to control it. Therefore, we should carefully utilize schools as powerhouses for resistance and empowerment. Students should also be inspired to become agents of change to stop discrimination at school and in society.

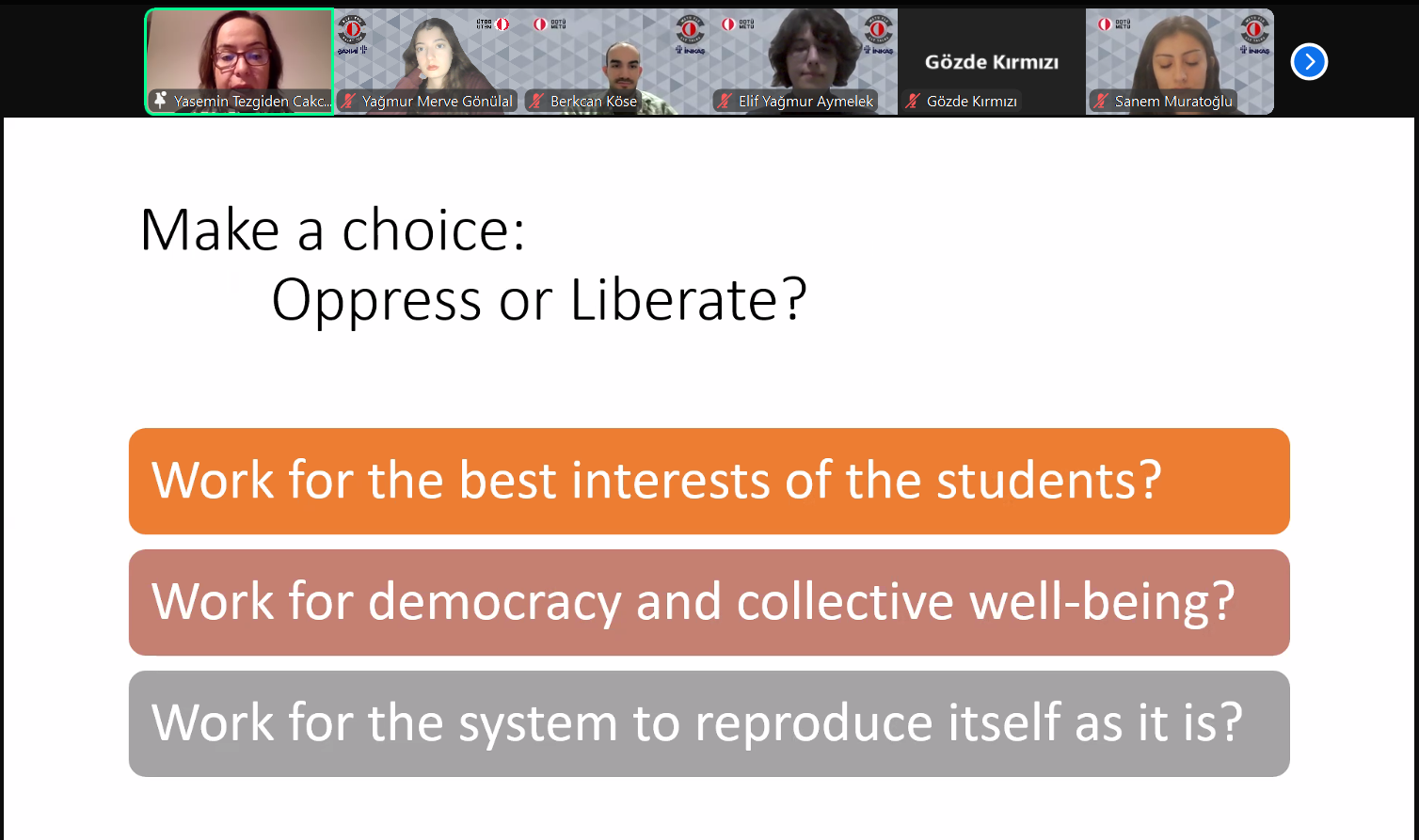

In a nutshell, critical pedagogy is dedicated to identifying undemocratic schooling practices and tries to help socially and culturally marginalised students and even teachers—not being part of that oppression but changing it. So, what roles do we have as teachers when it comes to helping make this change a reality? Tezgiden-Cakcak further examines this part through possible options: "You may choose to serve the system, or we might become the change, and we might become critical agents working for the well-being of everyone."

What about defining critical education? Tezgiden-Cakcak's main definitive answer to this question was, "To educate people who can think critically and cultivate their minds, who work for the good of others as well as themselves. Also, to transform society into a more equitable, just, peaceful, democratic one."

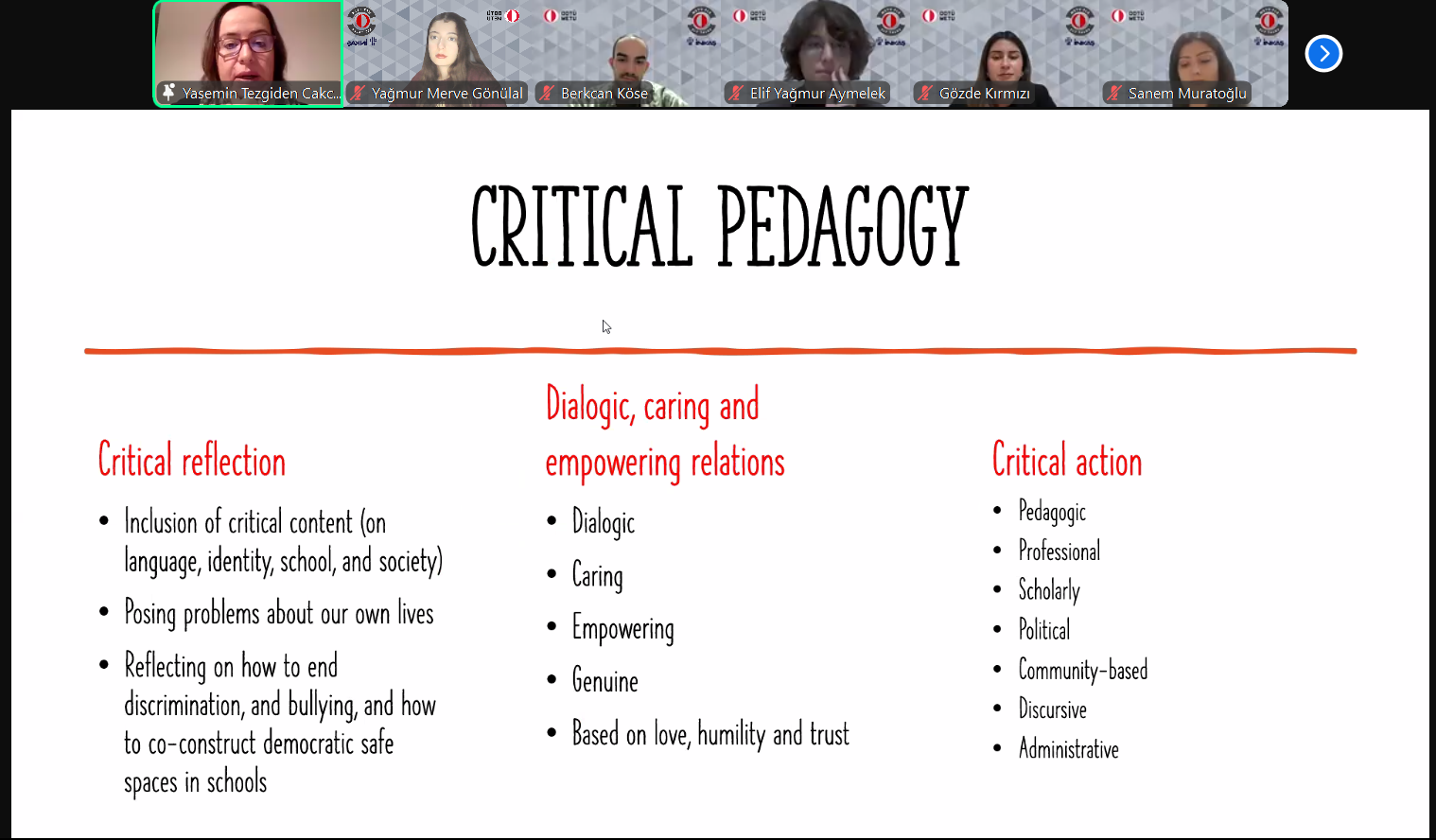

There are many possible ways to implement critical pedagogy in our ways of teaching. One shared by Tezgiden-Cakcak is by a well-known name within the critical pedagogy field, Paulo Freire, who highlights critical reflection and action. The key here is liberation, aka liberating ourselves from this oppression. Tezgiden-Cakcak expressed her idea regarding this part as "The terrible thing about oppression is: We are born in this system, we take it for granted, and we internalize it; sometimes we do not even realize it, let it be racism, sexism, or homophobia."

Although most of us are aware of these issues, we cannot deny several aspects that severely limit our ability to take action. Regarding this possible setback, Tezgiden-Cakcak mentioned, "Despite the potential risks, especially when it comes to challenging and criticizing the system under authoritarian systems with the freedom of speech highly limited, we should still take action. Since we live in a difficult time when we are overwhelmed with too many crises, if we do not take any risks, perhaps the risks will only get greater. Of course, we should assess the risky situation and act accordingly."

Another point to make here is that this can only be accomplished through solidarity and collaboration, as isolation would not be the solution. The system wants us to believe the phrase "You cannot change anything; you are just a teacher!" and accept our fate while leaving everything the way it is. However, according to critical pedagogy, this is wrong, as even if we cannot change the world, we can still impact it by changing our classrooms. Through unity in our classrooms and with many other colleagues in the field, having an impact is not a utopia.

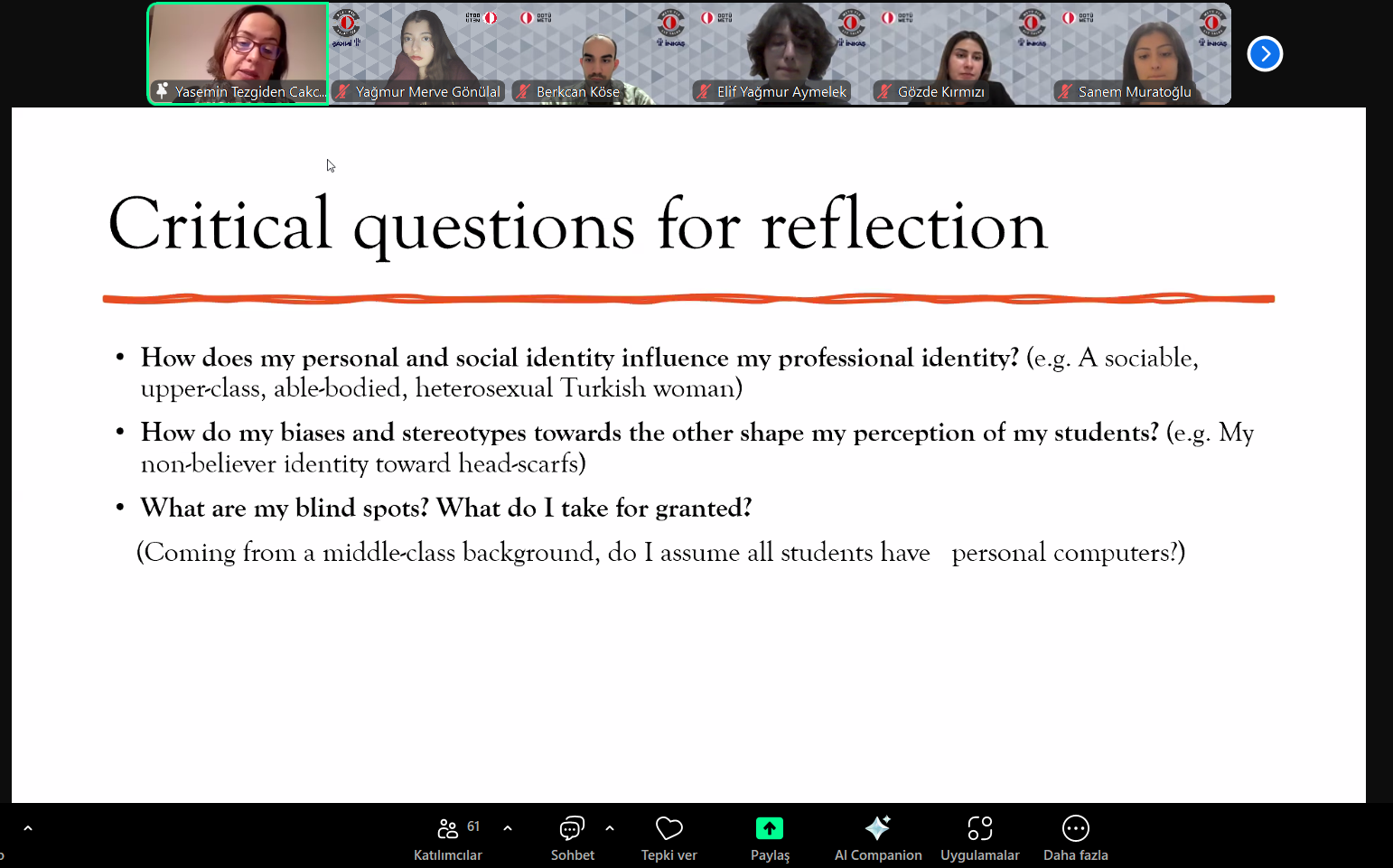

In addition, including specific introductions of words such as native speakerism or sexism through classroom discussions can be an example of how to start integrating critical pedagogy into our lessons. Depending on where you are and the hot topic, the focus can be shifted towards which things to focus on. We can also start through self-reflection by asking specific questions ourselves to better understand how our identity impacts our teaching. We should also think about our students and how they identify themselves. Even a student wearing glasses can be given as an example. Tezgiden-Cakcak also gave us another insightful example: asking students to create lesson plans based on the 4Cs: Critical, creative, communicative, and contextual.

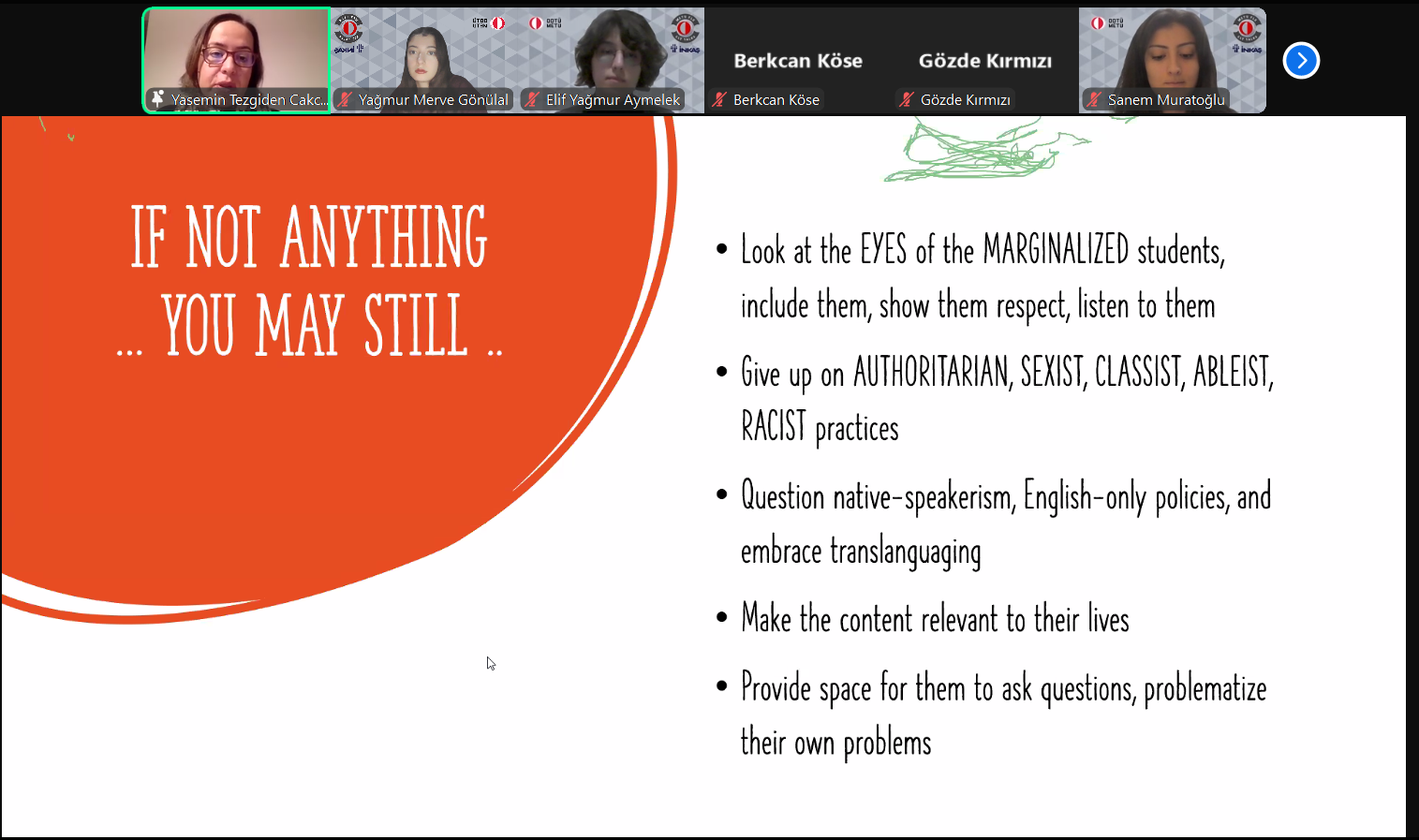

According to Tezgiden-Cakcak, similar to doctors, critical teachers should have "Do not do harm" as their first rule in their critical pedagogy journey. While being careful towards our influence on students' lives and perspectives, we should also not forget that even a small act of respect towards a student may mean the world to them. Furthermore, it would be a clever way of communicating a powerful message to the other students, teachers and the school despite not saying anything excessively.

To conclude our fruitful session, we would like to share an excellent thought-provoking quote shared by Tezgiden-Cakcak, inviting all of you to think and reflect further: "Education can never be neutral, and educators should ask themselves whom they are working for. Which side are you on: Oppression or liberation?"